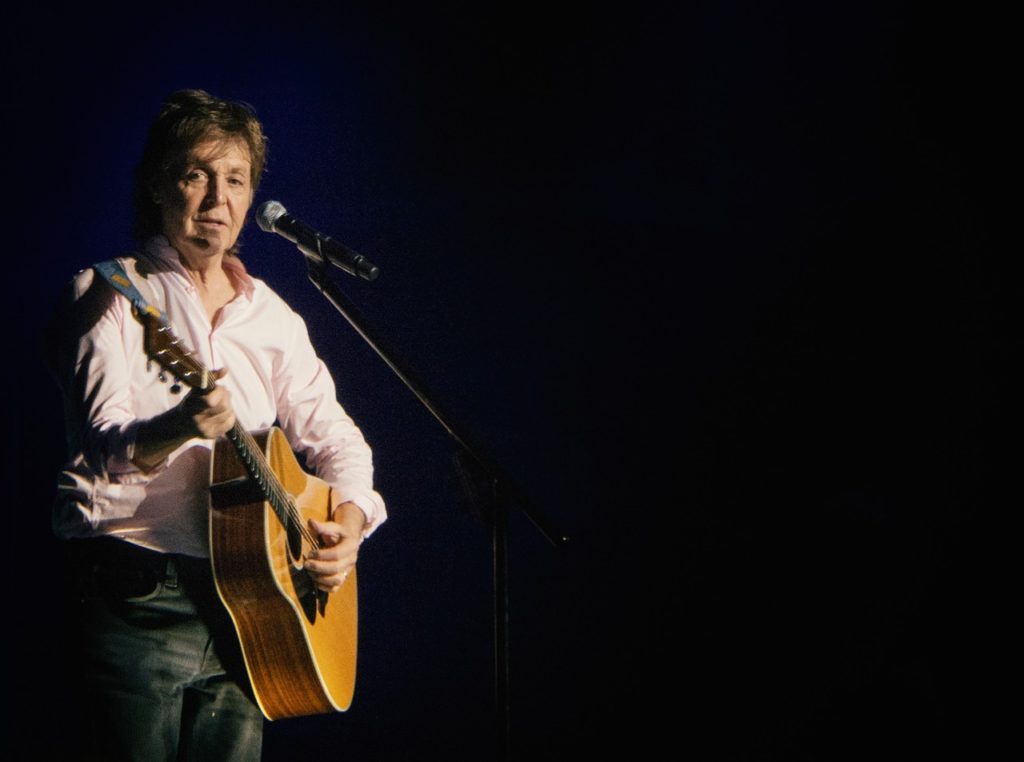

I watched Brian Moriarty’s Who Buried Paul lecture from 1999 the other week. This hour-long talk goes through the history of the idea Paul McCartney died in a 1967 car crash and all subsequent Beatles material carried clues about it. The talk itself is now twenty years old, but it carries some interesting ideas about how people connect to stories to create realities.

The talk was designed to illustrate how, from some bare bones of an idea, an audience will create a story. Humans seek patterns and meaning from random data points. Moriarty calls this concept ‘constellation’. Just as in ancient times a cluster of stars became a constellation and a goddess or god, so the randomness of a hand repeatedly appearing over Paul’s head became a symbol of his death.

I think this constellation process is working all the time, but becomes increasingly meaningful when things are changing in ways that increase uncertainty. I do not think it is a coincidence that the Paul is dead theory gained momentum in America in the turmoil of late summer of 1969.

I think you can see the process at work when fans interact with ongoing narratives. Some fans were not able to join Star Wars: The Last Jedi into their pre-existing patterns. Rather than tweak their theories, they rejected the film. Let’s not even go near the troubles the Paul Feig Ghostbusters encountered. In Doctor Who fandom, we developed fanon (fan canon) that has now become part of the series’ on-going narrative.

Since Moriarty’s talk was delivered, social media has exploded, and enables theories to find friends. Just as Moriarty and his friends reinforced each other in their reading of every clue, online bubbles mean people can now do the equivilent of scouring Abbey Road artwork but for news. Within minutes of the Notre-Dame du Paris fire being reported, fake news posts were claiming it as a deliberate attack. As someone’s position becomes more fixed, they seek more data points for that position and disregard others. Fake news content seeks to play with this instinct, and Moriarty almost captures it:

[There was] a statement from Paul in which he summarily dismissed the clues and declared that the whole matter was “bloody stupid.”

You might think that this authoritative appearance by McCartney would be enough to make the Paul-is-dead issue dry up and blow away.

It wasn’t.

So are there any benefits to this pattern-making habit? Again, Moriarty captures this in explaining why games developers at the turn of the millenium should care about a teenage obsession with a fake news story.

- If you are creating a fictional world, don’t define every single detail. Allow your worlds and your characters to have some spaces and some patterns which readers can then connect for themselves. But don’t be surprised if they create connections you don’t expect. And don’t clamp down on speculation: fans playing the game of creating a theory don’t want you spoiling their fun – just as Paul is dead fans continued despite his clear statement.

- If you’re writing a narrative for an organisation, look at it in the context of other communications within the business. What patterns, what constellations, can your audiences create with them? Where you need to be ambiguous for some reason, what theories will be created and need to be managed? Role play it, or test it with people to check what rumours it’ll start that you can’t see?